History often repeats itself, and the colonization of Africa is no exception. The advanced capitalist nations of the world, driven by economic expansion, sought new markets, resources, and geopolitical influence. The fires of industry and commerce had to be kept burning, no matter the cost. Wars have been fought for economic dominance before, and they will likely be fought again—because throughout history, man has killed man over wealth and called it business.

While some may romanticize the colonization of Africa as a pursuit of exploration and adventure, the reality is far more calculated. Expeditions that cost millions of dollars, countless lives, and years of effort do not happen without the expectation of profit or strategic advantage. For the European colonial powers, Africa represented:

Raw Materials: The continent was rich in gold, diamonds, rubber, ivory, oil, and fertile land, all of which fueled the industries of Europe.

New Markets: African colonies became forced consumers of European goods, ensuring that industrial production in Britain, France, and Germany remained profitable - this was especially noted by Egyptian economists during the British occupation of the state, where local Egyptian industry could not compete with the products from Europe due to the oversaturation of the market and filed bankruptcy .

Strategic Dominance: Control over Africa meant global power. The British sought to protect their route to India via Egypt and the Suez Canal, while France aimed to consolidate its hold over North and West Africa.

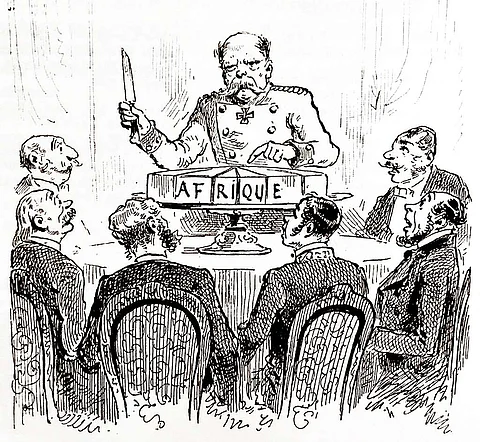

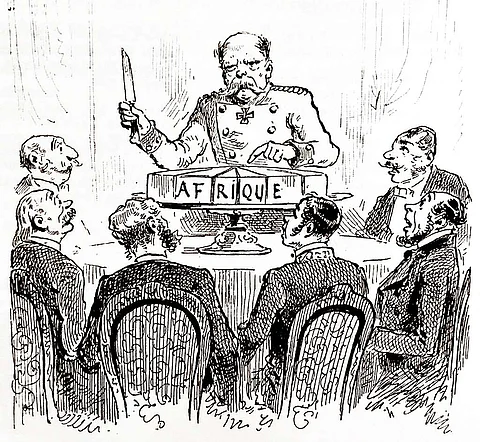

European colonial powers were not allies in this endeavor—they were rivals. Each empire sought to outmaneuver the others, securing as much land and influence as possible. The Berlin Conference (1884-1885) was an attempt to prevent all-out war between European nations by dividing Africa among them. But despite formal agreements, colonial expansion often led to military conflicts, revolts, and resistance from both Africans and competing European nations, for example, post-1882 invasion of Egypt saw the Fashoga crisis between the French and the British.

The brutal nature of colonial conquest reveals the true motives behind it. It was not about bringing civilization or fulfilling some grand mission of exploration—it was about wealth, control, and empire-building, anything else was either a byproduct or a secondary goal.

The events of the Scramble for Africa are not unique; they follow a pattern seen throughout history. Powerful nations seek new territories, exploit resources, and justify their actions through ideology, nationalism, or economic necessity. Today, global economic competition still drives wars, interventions, and resource struggles, proving that the cycle of history continues, the difference, though, is that national competitiveness is now fought more on the factory floor and business contracts than on the battlefield.

Understanding colonialism as an economic and political struggle, rather than a romanticized adventure, is key to recognizing its impact. The consequences of this period still shape Africa’s political and economic realities today, and they offer lessons for the world about the dangers of unchecked ambition, exploitation, and the pursuit of power at any cost.

While the economic and military advantages of colonizing Africa were clear to European powers, outright conquest had to be justified to domestic audiences. No government could openly declare that it was seizing an entire continent purely for profit and expect universal support. Instead, European authorities framed colonization as a moral and civilizational duty, using a mix of Social Darwinism, religious rhetoric, and anti-slavery narratives to justify their imperial ambitions.

During the late 19th century, European intellectuals widely embraced Social Darwinism, an ideology that misapplied Charles Darwin’s theories of evolution and natural selection to human societies. This doctrine suggested that some races were inherently superior to others and that it was the "destiny" of the "stronger" European civilizations to rule over the "weaker" African populations. By portraying conquest as an inevitable and natural process, European leaders sought to legitimize their imperial ambitions and frame colonial expansion as a force of progress rather than exploitation.

European powers also promoted the idea of a "civilizing mission" (mission civilisatrice)—the belief that they had a moral obligation to bring "progress" to Africa. This was especially effective in garnering support from the educated and religious segments of European society. Missionary groups were sent to spread Christianity, introduce European cultural norms, and establish Western-style education systems. Many genuinely believed they were uplifting African societies, while others used religion as a convenient pretext for conquest.

Another widely used argument was the claim that European colonization would end slavery in Africa. By the late 19th century, abolitionist movements in Europe had gained significant influence, and governments capitalized on this sentiment by portraying their colonial endeavors as efforts to liberate Africans from local slave trades. While it is true that European forces dismantled some indigenous systems of slavery, they simultaneously introduced new forms of forced labor, particularly on plantations, in mines, and in infrastructure projects

The Scramble for Africa was an event shaped by the economic and political ambitions of European empires, but in 2025, no ordinary person—whether from the colonizer or the colonized side—bears direct responsibility for these past actions. Instead of dwelling on blame, the focus must shift toward rectifying past mistakes and building a future where both Africa and Europe benefit from cooperation, mutual respect, and equal partnership.

History, if left unchecked, can become a cycle of grievances—a whirlwind of racism, pettiness, and self-destruction that serves no one. While historical injustices should not be forgotten, perpetual division and resentment only hinder progress. The challenge is not to rewrite history but to acknowledge it honestly while ensuring that its mistakes are not repeated.